Blog • Posted on Jun 19, 2024

How to Write a Research Abstract in 6 Simple Steps

Writing an abstract for a research paper is like distilling alcohol. We distill the key messages from our research manuscript (the mixture) into their own container (the research abstract). However, it's important that we avoid unwanted contaminants in our final product.

Let’s review the key components of a research abstract. At minimum, every research paper abstract consists of the following six sentences.

Research Abstract Template:

1. The Hook

The hook is the most important sentence you will write in your abstract. You decide whether you'll watch a YouTube video in the first few seconds. Likewise, your readers decide to read your paper in the first few lines.

The purpose of the first sentence of your research abstract is to introduce the reader to the topic. However, great writers go beyond this. Great writers use the first sentence of their research abstract to evoke curiosity.

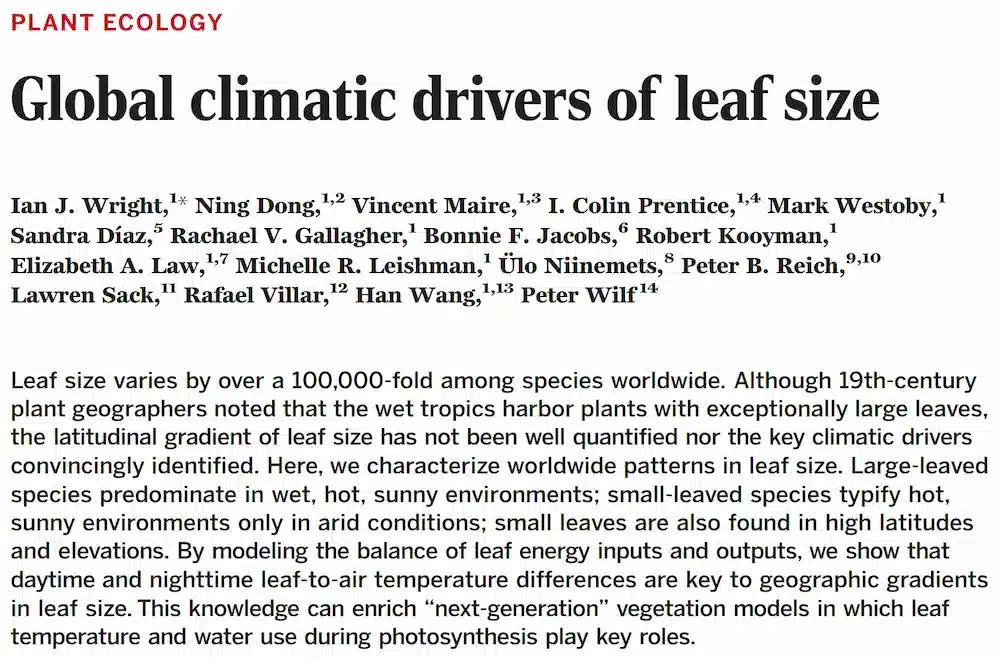

Let’s compare good hooks with great hooks, and take some learnings from a paper by Wright et al. 2017.

Since their study examined drivers of leaf size variation, they could have opened like this:

Leaf size varies considerably across the plant kingdom.

This is a perfectly acceptable introduction to the topic of leaf size variation. But it doesn’t evoke curiosity. Nor does it pique interest.

Here's what they wrote instead:

Leaf size varies by over 100,000-fold among species worldwide.

Now that’s better. But why?

- The hook is short; and

- It evokes curiosity

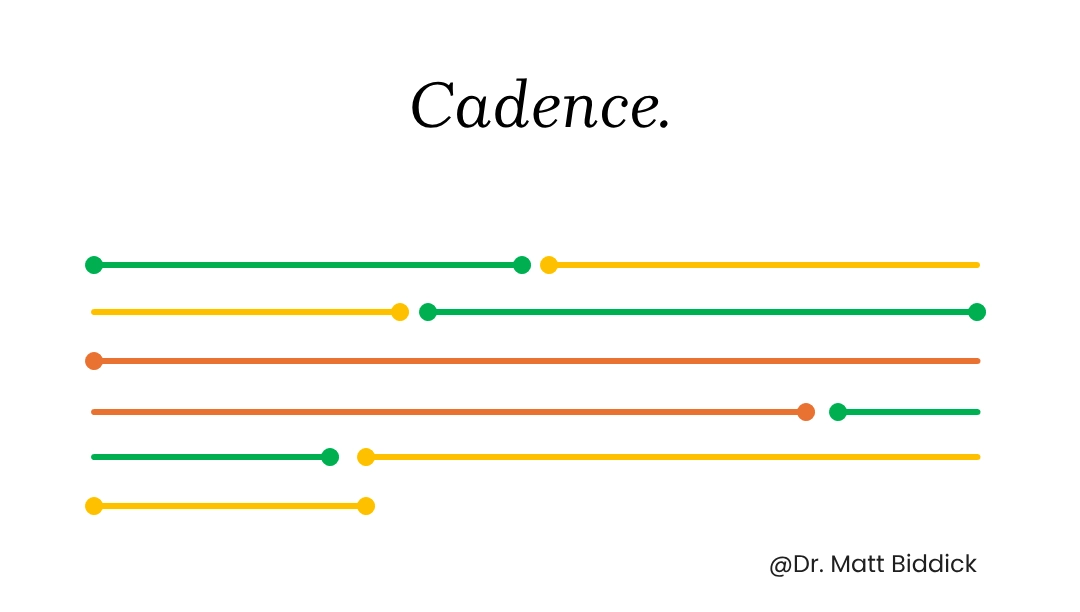

The hook is short; really short. That’s important because it helps with cadence.

Cadence is the tempo or rhythm of your writing. Authors who use cadence well mix short, medium and long sentences to maintain reader attention.

Your goal should be to mitigate the attrition of reader attention. Long sentences tax the reader. So it’s important to give them a rest. Very long sentences should be used sparingly and be accompanied by shorter sentences to give the readers’ mind a break.

Our improved hook also features a curiosity-evoking fact. The authors could have simply stated that leaf size varies greatly, but instead chose to quantify it. Why?

Because it evokes curiosity.

Does leaf size really vary 100,000-fold globally? That’s a lot! Picture that for a moment. There is an urgent desire to know more upon reading this hook.

- Which plant has the smallest leaves?

- Exactly how small are they?

- What about the biggest leaf?

- Why would a plant bother to make such enormous leaves?

You see how our improved hook has achieved the same task of introducing us to the topic but additionally piqued our curiosity?

When possible, use impactful facts about your study topic to pique reader interest and evoke curiosity.

2. The problem or knowledge gap

Next up we need to state the issue at hand. This can be either a known problem or an existing gap in our understanding of the phenomenon. This really is the crux of our storyline because it sets the tone for the rest of the research paper.

What is the ultimate contribution of our study to furthering our understanding?

Sometimes the gap is quite niche and therefore requires us to set it up with an additional sentence. That’s fine. Just make sure you’re writing with this purpose in mind.

Sentence 2 almost always states with “however”, “despite”, “although” or some other word/phrase that embodies this sentiment.

Our case study sheds light on some of the drivers of leaf size variation among species. Thus, to set ourselves up for success, we need to clearly articulate that the environmental correlates or evolutionary drivers of leaf size variation are not well understood.

Anything approximating this will do. However, we must tread lightly here.

If some drivers of leaf size evolution are well understood, we must speak modestly about our lack of understanding. On the other hand, if we genuinely don’t know a thing about what drives the evolution of leaf size, then by all means go nuts.

Let’s see how Wright et al. navigated this:

Although 19th-century plant geographers noted that the wet tropics harbor plants with exceptionally large leaves, the latitudinal gradient of leaf size has not been well quantified nor the key climatic drivers convincingly identified.

They highlight the two contributions that their paper is going to make. Namely, (1) the quantification of the latitudinal gradient of leaf size variation globally; and (2) the identification of key climatic drivers of such variation.

The word “driver” can sometimes be problematic. Some readers will take issue because it insinuates that we know emphatically that the correlates are driving the phenomenon under study. In reality, we don’t know.

Notice how this sentence is quite long. But remember back to our discussion of cadence - this works because the hook was so short. We aren’t fatigued, so a long sentence is no issue.

We’re also about to be hit with another one-liner in sentence in sentence 3.

3. How you solve the problem or fill the gap

Here, we characterize worldwide patterns in leaf size.

The authors have achieved the goal of sentence 3 with the utmost brevity. And brevity immediately following a long sentence is warmly welcomed.

There’s not much else to say here. Sentence 3 is a no-brainer. So enjoy it and move on to sentence 4.

4. How you did it

This is where our authors have deviated from the typical format. They have elected not to describe exactly how they have performed their study and instead get straight into what they found.

This study was published in Science Magazine; one the most competitive journals in the World and extremely limited for space. So, the authors have put more focus on what they found than how exactly they found it.

Were this paper to have been published in a more mid-tier journal, they may have elected to use another sentence to outline their methods. This is something you must judge on a case-by-case basis, depending on what level of journal you are aiming for and their specific requirements.

Should you choose to describe your methodology, keep this to one sentence at an absolute maximum. Another approach would be to merge sentences 3 and 4.

All of the above are valid strategies.

5. What you found

We have arrived at the meat of the sandwich that is our research abstract - our findings. Think of sentences 1-4 as a necessary warm up to your delivery of what you found. The readers’ mind has been sufficiently primed.

They understand what we are talking about, what’s lacking in our understanding of the phenomenon, and that we have made some effort to resolve this. Now it’s time to hit ‘em with the good stuff.

This will almost always be more than one sentence.

Think back to our analogy of distillation. We need to distill the key findings of our study. Ignore the temptation to include marginal or supplemental findings that aren’t central to your storyline. These are (quite literally) contaminants in your research abstract.

Let’s review our case study:

Large-leaved species predominate in wet, hot, sunny environments; small-leaved species typify hot, sunny environments only in arid conditions; small leaves are also found in high latitudes and elevations. By modeling the balance of leaf energy inputs and outputs, we show that daytime and nighttime leaf-to-air temperature differences are key to geographic gradients in leaf size.

The authors have elected to squeeze 3 results into a single sentence by using a list. This breaks our typical format somewhat, but it’s an important lesson in how to pack more into less.

They have also somewhat merged the purpose of sentence 4 into their second results sentence by including how they got their final result.

Great writers can break free from the traditional resaerch abstract template because they understand the purpose of each sentence and can achieve the same outcome using different means.

This comes with repetition and time, so don’t stress if this doesn’t come naturally at first.

6. What it means

Finally, we need to articulate what our findings mean for the discipline and our wider understanding. Just like our result sentences, there are many possibilities here. What’s important is that we limit this to the most important insight from our study.

Try to keep this to one sentence when possible.

This knowledge can enrich "next-generation" vegetation models in which leaf temperature and water use during photosynthesis play key roles.

Wright et al. chose to highlight how their results inform modern vegetation models, which are increasingly popular and used in biodiversity forecasting.

This simple one-liner nicely closes the loop and leaves us with a feeling of fulfillment. The study has shed light on something we previously had little understanding of and additionally improved our ability to forecast future biodiversity dynamics - how neat!

Take your writing to the next level

As you write your research paper, consider seeking expert guidance. Services like ours offer personalized assistance to researchers, aiding all aspects of paper writing and facilitating swift and efficient journal handling.

The publishing landscape can be brutally competitive, and the journey from abstract to publication is often challenging. Whether it's creating a skeleton for your manuscript, finding the story of your results, or editing a completed draft, having a knowledgeable ally by your side can make all the difference.

Dr. Matt Biddick is a Senior Consultant at RURU. You can book sessions with him here.